Archive for FAQs

December 6, 2007 at 6:59 pm · Filed under FAQs

Probably the most common problem I see among RV’ers is the inability to back up their trailer. We meet tons of people who camp only where they can find a “pull thru”, and will go to great lengths to avoid ever getting into a situation where they might have to back up. We usually encourage them to give it a try, but I don’t think our advice has ever been accepted.

Even among people who do back up once in a while, it can be challenging. Single-axle trailers back up differently from double-axle trailers, and longer ones are different from shorter ones. The type of hitch you have can make a small difference too. Backing up requires you to have a sense of how the trailer will react to various inputs from the tow vehicle, while simultaneously watching for signals from your assistant, and checking for obstacles in three dimensions. It can be very challenging.

We’ve been lucky enough that in all our travels we have never dinged the trailer during backing, but that’s rare. Most everyone has a scrape or dent somewhere to point to, showing the time they nudged a picnic table or didn’t see that low tree branch. It’s easy to dent the soft aluminum of an Airstream and not even know it’s happening.

But learning how to back up is a great reward. Often we come to campgrounds where we are offered a pull-thru site or a back-in site for a few dollars less. We always take the back-in and save the money. I figure it’s payback for all the practice.

My blog post yesterday got a few comments from people admiring the backing-in job we did here at Brian and Leigh’s. It was one of those great moments when, under the pressure of witnesses standing by, we just swung it in there in a single pass and ended up exactly where we wanted to be, inches from a concrete block wall and a house. Blog reader Dirk asked if I had tips for others, or if this particular backup was a “breakthrough moment.” Actually, I hadn’t thought any further about it until we got the first blog comment this morning. It was just another parking job to us, but remember that we’ve been in our Airstream over eight hundred days. In all that time, I’ve gotten plenty of practice — and practice is the real secret.

I suppose there are a few other tips to share. The most important is to have a partner to help if possible. You could call him/her your “backing buddy”. Typically this is your spouse. You can’t see very well behind your trailer, and it’s easy to overlook obstacles. Your partner stands near or behind the rear rib of the trailer, well off to the side, and directs you in. Tell your partner that if she can’t see your face in the side mirror, you can’t see her either. The partner should stand on the inside of the turn, and in some places this means she has to tell you to stop so she can move to the other side.

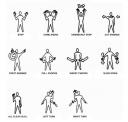

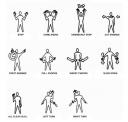

Lots of people use walkie-talkies but we just use hand signals like those used at the airport. Make sure you both know the proper signals and don’t spontaneously make up new ones. The signals should use your full arms, not just hands, so the driver can see them clearly. You only need four signals: left turn, right turn, come ahead, and stop. For stop, we use crossed forearms (forming an X) because they are easier to see. You might also want a fifth signal, “go ahead,” when the backing isn’t going well and you need to pull forward again.

Lots of people use walkie-talkies but we just use hand signals like those used at the airport. Make sure you both know the proper signals and don’t spontaneously make up new ones. The signals should use your full arms, not just hands, so the driver can see them clearly. You only need four signals: left turn, right turn, come ahead, and stop. For stop, we use crossed forearms (forming an X) because they are easier to see. You might also want a fifth signal, “go ahead,” when the backing isn’t going well and you need to pull forward again.

The nice thing about hand signals is that they impress the hell out of people who watch us. They look very professional and it helps scare off people who like to “help” you back in.

I have only one tip regarding “help” from strangers. DON’T ACCEPT IT unless you really have to. If you have a partner, use the partner who you are accustomed to and can trust. Most people are well-meaning but since you don’t know them, you really don’t know if they are going to back you into a tree or confuse you with misleading advice. My friend Rich Charpentier has two dents on his Airstream, both courtesy of people who (on different occasions) tried to help him back into campsites. Not surprisingly, none of those people offered to pay for the damage that resulted from their bad advice.

Once in a while we have managed to insult people (unintentionally) who had a serious desire to “help” us back in. I remember a particular time when someone wouldn’t accept my standard reply of “No thanks, I have Eleanor to help me and we’re used to working together.” He continued to direct me aggressively and loudly toward an overhanging branch while I ignored him and followed Eleanor’s advice. When the parking was done, he was miffed, but we got to know each other the next day and eventually became friendly.

There’s a popular technique taught to newbie trailer owners: put your hand on the bottom of the steering wheel and turn it in the direction you want the trailer to go. This tip plays a part in the 1950s Lucy & Desi movie called “The Long Long Trailer,” when Desi Arnaz is being shouted at by dozens of well-meaning relatives while he backs down a long driveway. The technique works when there aren’t a lot of relatives around, but I don’t do it. Find a technique that works for you and stick with it.

Backing up is best done slowly. Don’t let anyone rush you, not even traffic you might be blocking. They can wait. Going slowly allows you to learn how the trailer is responding, and it gives you partner a chance to check clearances as you go. Remember to have the backing buddy check above and below the trailer as you go. Overhanging tree limbs and curbs will sneak up on you if you aren’t careful.

Finally, don’t back up at night until you are well-practiced in daytime. Even then, go extra slowly at night and check your clearances multiple times. You’ll need good flashlights too, because the backup buddy will be invisible. At dusk, like when we arrived here at Leigh and Brian’s house, I’ll get out of the truck three or four times during the backing process, to check my progress and confer with Eleanor. Even after hundreds of backing operations, we’re not immune to the possibility of running into something.

In fact, we’re far from perfect backers. Many times I’ll get the “go forward” signal from Eleanor and have to try again, sometimes three or four times. The keys are to stay calm, don’t fight, and go slowly. You’ll get in there eventually.

December 2, 2007 at 8:48 pm · Filed under FAQs

In years past we’ve come back from a vacation and had to face grim aspects of “real life”, which usually included freezing weather, a pile of backed-up mail and phone calls, and a house that needed some attention right away. In this case, coming back from Hawaii has been a relative pleasure because we landed in Los Angeles where the sun was shining and the temperatures were in the 60s. It was less of a shock to the system, coming from humid days in the 80s.

But the best part was coming back to the Airstream. At last, a bed I can sleep in. Our own kitchen again. No more unpacking and re-packing. No more people at airports telling me that my bottled water is too risky to carry on board an aircraft. My own DVD collection rather than pay-per-view on the hotel TV. It’s great to be back home and yet still able to travel.

To be fair, there were a few things to deal with. We had removed a lot of stuff from the truck and put it in the Airstream for safekeeping, including three bicycles, some tools, the sewing machine, etc. With Los Angeles traffic we got back to our storage spot after dark, and we couldn’t stay in the storage lot overnight, so we had to re-arrange everything, hitch up, and tow about 1/4 mile to a campsite. But in 20 minutes or so we were set up for the night, which is about the amount of time it took us to get checked into our Waikiki Beach hotel, get a parking pass, and unpack in our room. We’ll keep the Airstream hitched up overnight and pull out tomorrow to points as yet undetermined.

One small lifestyle change is the need to re-adapt from the hotel shower to the RV shower. In the hotel, we had a cascade of water, and hot stinging needles if we wanted them, flooding the tub so quickly that the drain couldn’t keep up. This was the sort of shower that people seem to like, not so much because they get cleaner but because it feels like a “spa” experience. You don’t get pummeled by hot water much in an RV, and that seems to really bother some folks.

This is probably why I get so many reports from people saying that their “gray water” tank doesn’t last long enough when they are not connected to a sewer hookup. (The gray tank is the tank that holds used water from the shower and sinks.) It’s true, the tank is never as big as you’d like it to be, but with a little careful conservation you can last a long time. The problem I usually find with people who are filling the tank quickly is that they’ve never learned to conserve water.

There are two things that really fill up the gray tank fast: Showers, and dishes. A lot of people switch to paper plates when they are trying to make the gray tank last a long time. We’ve done that, but we’ll also use campground dish-washing facilities if they exist, as we did at Yellowstone.

You can do the same with showers if you are in a campground where they are available. Some people use the campground shower religiously, because they don’t fit in the small travel trailer shower, or because they just prefer the “home style” shower when it is available. Personally, I like my Airstream shower and I hate using the campground showers, so I’ll go to some effort to be able to shower in the trailer.

This means the “navy shower” is essential. It’s a simple technique: turn on the water, get wet, turn off the water. Then soap up everything, and rinse off quickly. Get really good at it, and you’ll find you can take a complete shower in about three gallons, or about 90 seconds of running the water. That makes you an Admiral in the Navy Shower Fleet.

Even an Able Seaman should be able to do it in less than six gallons (just over two minutes). Get it down to a flat two minutes (five gallons) and you’re a Lieutenant, or four gallons (a minute and a half) for the Commander’s rank. This assumes you have a typical RV showerhead that lets 2.5 gallons per minute through.

If you blow it, the Airstream has a built-in warning sign. The hot water tank is usually six gallons. If you start feeling cold water, you’ve used all six gallons plus a bit more (because the tank is constantly re-heating) and you’ll soon be walking the plank when the rest of the family finds out. Even in a full hookup campground where you don’t have to worry about running out of water or filling the gray tank, the six-gallon limit still applies.

The other thing you need to know is the size of your gray water holding tank. Ours is a fairly roomy 39 gallons, which means all three of us Admirals can take showers in a total of less than 10 gallons, giving us three showers each plus some tooth brushing and dishes, before we run out of holding capacity.

It’s really not hard to learn the navy shower technique. Camping without a full hookup does require some small sacrifices, but you can still have a satisfying shower. The inability to stand under a spray of hot water for ten minutes is nothing when you realize that small sacrifice enabled you to walk out your door into the landscape of a great national park, or a quiet beautiful place far from crowds.

November 13, 2007 at 8:52 pm · Filed under FAQs, Travel / lifestyle musings

As I travel I’ve been asked by friends to keep my eyes open for certain models of vintage Airstreams that are for sale. Out west I find some of the best Airstream hunting, because around any corner there can be a well-preserved vintage trailer sitting in a low-humidity climate, just waiting for someone to come by. California is not the best spot because prices here tend to be high, and only a little of the state is truly arid, but there are still plenty to be had.

Roger heard about a 1978 Airstream Excella 500, 31 feet long, sitting in a salvage yard not far from Visalia. After dropping off the Nissan for its expensive 60,000 mile service, we drove over to the yard to check out the trailer and document it for anyone who might be interested. Roger posted my photos and his on Flickr.

The seller is asking for $7,200 or best offer, which seems a tad high, but the trailer is very well kept. It was clearly loved by someone and maintained. The interior is all original except for fabrics, and it has a good roomy floorplan up front, twin beds amidships, and a spacious rear bath. The body is in good shape with no major dents.

The seller is asking for $7,200 or best offer, which seems a tad high, but the trailer is very well kept. It was clearly loved by someone and maintained. The interior is all original except for fabrics, and it has a good roomy floorplan up front, twin beds amidships, and a spacious rear bath. The body is in good shape with no major dents.

Like a lot of 1970s trailers, it has storage in abundance, tambour doors everywhere, extensive clearcoat peeling, tired axles, fogged Vista-View windows, and lots of potential. I’d expect to drop another $4-5k into it quickly for axles, brakes, tires, leak fixes (I’m sure there are leaks somewhere), new awning fabric, and a bit of floor rot repair near the entry door. A more complete restoration that repaired or replaced the fogged windows, replaced all the fabrics, and included a budget for appliance replacements would probably run $10-20k depending on how nice you wanted it. A full-blown restoration to get it perfect and polished … well, that could cost anything.

The point is that an Airstream can cost almost anything. You can certainly get going on a budget as low as $5k (we did). For a lot of people, the best course is to take an “OK” trailer like this one and upgrade it slowly as you use it. If I were looking for a longer trailer that I could start using right away, I’d consider this one with a working budget of about $10-12k for trailer and initial fixes.

While we were poking around at the salvage yard we also spotted a very tired 1976 Airstream Caravanner 25 (needing a complete restoration and sporting some poorly repaired rear dome segments), and this “so ugly it’s cute” 1962 Dodge 880.

While we were poking around at the salvage yard we also spotted a very tired 1976 Airstream Caravanner 25 (needing a complete restoration and sporting some poorly repaired rear dome segments), and this “so ugly it’s cute” 1962 Dodge 880.

The Dodge is all original. It’s the classic story of the car owned by a little old lady and used only occasionally. 34,000 miles and it shows just a little patina in the form of small rust areas around the corners. It runs and the interior is excellent. I especially like the funky push-button transmission.

I’m intrigued by the idea of using a 1960s car as a tow vehicle for our 1968 Airstream Caravel, but I’m not buying this one yet. The seller wants $6,500 if you’re interested. Photos are also on Roger’s Flickr album.

Tomorrow we are moving off. We have mooched a few very nice nights with Roger & Roxy, gotten our errands done, eaten coconut cream pie, and caught up mostly with business. It’s been fun and relaxing being here.

Now we’re heading to the coast to meet up with some Airstream folks who flagged us down a few days ago on our way out of Yosemite: Cynthia, Dennis, and 7-year-old Madison. They’ll courtesy park us at their house, so this is a a great low-cost week, but that’s not the reason we’re going there. It just looks like fun. Good enough reason.

November 5, 2007 at 12:47 am · Filed under FAQs, Tips & Ideas

It has been a very pleasant Sunday. Our overnight parking spot on the street in front of photographer Doug Keister‘s house turned out to be very quiet. Doug gave us a quick tour of Chico, and then did a little photo shoot of Emma for possible inclusion in one of his future projects. By 11:30, we were shoving off and moving south on Rt 99 again, toward tonight’s courtesy parking spot in Amador City, CA.

Courtesy parking is one of our favorite modes of “camping.” When you park at someone’s house, you often get the benefit of a fun visit and great insider tips about the local area. Since we’ve been in campgrounds a lot lately, I’ve been looking forward to a few nights of courtesy parking. It makes a nice balance, in addition to saving money.

But campgrounds still constitute the bulk of our nights on the road, so it pays to have a solid understanding of what to look for in a campground. I know from talking to other RV travelers that there is a lot of confusion about this. I’ve rarely talked about the differences between campgrounds, but perhaps it’s time. Campgrounds are not all made equal.

With time, you can develop a sense of what sort of camping experience you’ll get just by looking at the entrance to a campground, or from reading its description in a guide. If we want a scenic, natural, and peaceful experience above all, we tend to avoid places with hundreds of sites, those that are visible from the Interstate, and those with high percentages of permanent residents. Often just the appearance of the entry gate or sign will give a solid clue to the experience that awaits within.

Terms in guidebooks like “big rig friendly,” “laundry, store, and pool,” and “all pull-throughs” are hints that the campground will offer convenience but probably not natural settings. It’s up to you to decide what you want that night. We vacillate between seeking convenience and connectivity (cell phone, Internet), and solitude and natural beauty. In some cases we can find both, but more often a compromise has to be made. My general rule of thumb is that desirability of a spot is inversely proportional to the likelihood of getting online. When we do find a place that offers it all, we stay longer.

There are other clues as well. For example, campgrounds that participate heavily in deep-discount membership programs are generally not in highly desirable locations, but there are exceptions. Most often we find they are at the edge of town or a bit run down. Still, if you’re a member of Passport America, Happy Camper, or other similar programs, the discount often makes up for the minor deficiencies of the campground.

State parks are almost always pleasant but you need to understand each state to know what to expect. In Florida, for example, all state parks with camping have 30-amp electric. In Vermont, none do. Older state parks built during the CCC era (1930s) generally have narrower roads and smaller sites, but nicer settings, so an abundance of CCC-type architecture (stone walls for example) is a clue.

Campgrounds that are predominantly mobile home parks are almost always best avoided. While the sign may say “RV’s welcome”, we’ve never seen one that we’d want to spend money to stay in. However, a lot of RV parks have a small area of fixed or mobile homes off to the side, and those are usually fine.

“55+” is a glaring clue. Since we aren’t over 55 years old, and we travel with a child, we regard “55+” as a sign that the park is filled with stodgy people who have lost their appreciation of children. I appreciate the warning. We’ll go somewhere else. (It’s a shame that these discriminatory “55+” parks are such a plague in Arizona and Florida, however.)

National Forest Service campgrounds, Bureau of Land Management campgrounds, and Corps of Engineers campgrounds can be found in some really spectacular natural areas, and they’re usually cheap. They tend to be in the boondocks. Finding one near where you want to be can be tricky, but if there’s one nearby, they are often pleasantly surprising.

If you’re the sort of person who likes to eat at chain restaurants everywhere you go because you know what to expect, you’ll love big camping chains like KOA. But if you’re the adventuresome type that likes to try the local food wherever you go, you’ll soon learn the subtle cues that lead you to the type of stay you want.

Tonight we are parked at Rob & Sadie’s house in the tiny gold-mining town of Amador City CA. Since we’ll be here two nights, I’ll tell you all about it tomorrow.

July 19, 2007 at 5:39 pm · Filed under FAQs

This is the third and final part in a multi-part series about how we got started as full-time Airstream travelers. The first part can be found here.

Some people cannot see their way to lowering their expectations of certain creature comforts or perks of our satiated society. They want to retain all the familiar benefits of home (the gardening club, yards of indoor personal space, unlimited hot showers) while traveling. Such people are doomed to spending their vacations in hotels, and paying top dollar for their travel. I pity them.

We often forget that everyone in America is royalty, relative to much of the developing world. As one potential immigrant said, “I want to live in a country where the poor people are fat.” We forget that even “starving” college students enjoy a lifestyle far above much of the world’s population. We have technology to enable nearly constant communications, safety nets galore, and the path is well paved by those who have gone before. We are blessed with enough abundance that most of us have the option to travel, whether we choose to exercise it or not. Rarely can I buy the arguments that “we can’t afford it,” or “it’s too hard” when people are speaking of heading out to travel full-time. It is more a matter of adjusting expectations. Changing yourself is more of a challenge than coming up with money.

For example, we had to adjust to life in 200 square feet. Three people in a trailer full-time requires a higher level of cooperation and togetherness than in a house. The compensation of course is that the world is your living room. Sitting in a trailer in one spot can be deadly boring, but if you travel the scenery always changes and interior space becomes less of an issue. I think people are buying larger houses these days because they spend more time inside sheltering themselves from other people and potentially distracting experiences. For some of us, going larger is an unsustainable strategy. At our house we had 2,900 square feet and I was driven nearly mad with cabin fever each winter. The next winter I was happy to share 200 square feet with my family in the Airstream. I had discovered what really mattered to me, and it wasn’t square footage.

Interior space still matters, but the lack of it can actually be a benefit. I was asked about this by the marketing head at Airstream, who wanted to know how a family of three could survive in such close quarters for months. “It has made us more polite. We say “˜excuse me’ a lot,” was my answer ““ which was true, because when every cubic inch has to serve a purpose, inevitably someone else is occupying the space you need. But a better answer was given by a couple in California: “We bump into each other a lot. We like bumping into each other.”

The rewards for all the minor adjustments are intangible but satisfying. I said that the genesis of our travel was necessity, but there is a deeper motivation that stems from our desire to be free. The winter before we put our house up for sale, we spent three months in rented Florida condo. At that point the magazine was a struggling start-up, and we were living solely off savings. But every day seemed worthwhile and full of beauty, and finally one day I realized that freedom was more important to me than things. I was enjoying life more despite living with less.

Our house was stuffed with objects that didn’t really add value to our lives ““ to the contrary, when we got back from Florida Eleanor and I were dismayed to re-discover all the stuff we owned that served no practical purpose on our lives. While we were gone, we missed none of those things, and in fact had forgotten they existed. These things were psychological anchors, but not only in the sense of giving us a home base. They were also obligations that held us fast, keeping us from exploring by their sheer weight.

We talked about this sensation, and realized that the stability we had built for ourselves had a dark side. We had the security of home and the insecurity of worrying about mortgage payments. We had the memorabilia of generations past, and the obligation to keep it dusted. We had enjoyed the income that comes with success, and felt the unyielding demands of careers. In short, the security we had felt was an illusion. Was there an alternative? Could we give up the trappings of a traditional life to find something else?

Based on this experience, I resolved to trade money and things for freedom and experiences, and that was later the foundation of our decision to sell the house and plunge headlong into the magazine. That led to the second decision to live the traveling life, and ultimately our satisfaction proved the thesis: freedom is more important than things, at least for us. Our net worth on paper is less than it was two years ago, but our satisfaction with life (a more heartfelt measure of net worth for most people) is dramatically higher.

Besides, there have been practical benefits. Full-time traveling turned out to be cheaper than staying home. The tallying of our expenses has become an almost guilty pleasure because money deposited in the checking account tends to stay there, rather than being vacuumed out by household bills. Not only did our decision to travel give us more capital to invest in the business, it seems unfair to everyone else that we get to see America, Canada, and Mexico at our own pace, while spending far less each month than for a week at Disney. Considering how broadening the experience has been (and continues to be), it has been the bargain of the century. This is how full-time travelers get addicted. They recognize that re-settling in a fixed location and having to buy furniture again is the real compromise, and so they put it off, sometimes for years.

That is precisely what happened to us. Four months into our “six-month” voyage, somewhere between the redwood forests of northern California and the sea lions of southern California, we suddenly felt the slippage of time and realized we weren’t ready to stop. In four months we hadn’t seen much relative to the vastness of North America and, having tasted the freedom to explore at our own pace, the idea of settling down to build a house and leaving the rest of the world to explore some other day was horrifying.

This was not a lightly-made decision. The home-building season in Vermont required us to start construction in May in order to be finished by winter. Staying on the road for “a few more months” effectively meant we’d lose the building season until the next year. Thus, our choice to become official “full-timers” meant we’d be living in the Airstream for a total of 18 months at a minimum, and even longer if we lived in it during house construction.

Still it was a clear choice. Our daughter Emma was young enough (age five) that homeschooling was easy. We had no obligations requiring us to be near home base. In a few years, school, family obligations, medical issues, and even the magazine might require us to stop traveling. It seemed best to grab the opportunity while it was still available. We were undeniably no longer just voyeurs to the full-time lifestyle, but committed in a fundamental way. We had tip-toed our way in, from buying the first Airstream, then deciding to commit to a business that would enable travel, through the advancing phases of selling our home, delaying a replacement, and finally admitting the truth: we were happier with only the things we could fit in a 30-foot trailer and endlessly varying scenery. I called Airstream, wrote a check from our house fund, and a few weeks later the trailer was officially ours.

From this point on, Eleanor would explain to the incredulous and skeptical people who often visited us, staring up and down the 26 feet of interior length, “It’s not a house, but it is our home.” Few people understood, but it didn’t matter. We didn’t need validation from others. It was about what we knew worked for us.

Of course our plan didn’t work out nearly as we expected it to. Plans rarely do. We started out devoted to making memories, and in that we were successful. But we found that life in an Airstream included the moments that were lonely and frustrating, just like in stationary life. There were moments of insecurity where we feared having to go back to “the real world” and there were moments when we saw sadness in the other’s eyes and knew that perhaps we were reaching the end. One night in Florida we sat up until 2 a.m. talking while a heavy fog blanketed the trailer and the surf pounded the shore outside our window, whispering to each other about fears and finances, health and home, and the sum of it all. These are elements of life, and they must be embraced along with the high points. We experienced these things and grew with each challenge, because we had to in order to keep the adventure going, and we loved the adventure.

Eventually the trip mutated from an adventure into a lifestyle, and then something beyond lifestyle. It became one of the most remarkable events of our lives, and the formative part of Emma’s childhood. “Trips” come and go and they are often the source of wonderful memories, but adopting an entirely new lifestyle is much different. The change gets into your heart, and affects your values, your perception of the world, your understanding of society. You can’t go back to being who you were before. It is no exaggeration to say that in many ways, we were re-invented by travel.

Reading this, you may be skeptical that an extended trip in an RV can be so influential. My purpose in writing what is to follow is to show you how the change gradually came upon us, drawing on the notes I took and the daily weblog I wrote during more than two years of life in a house with wheels. You can travel with us, to dozens of national park sites in 42 states, from two hundred feet below sea level to 12,000 feet above, and meet hundreds of people of every description. If I can convey the feeling of each experience rather than just the sights and sounds, I may succeed at explaining the changes that occurred inside us.

Perhaps rather than asking “How did you get started?” the question should be, “Why did you stop?” At this writing, we haven’t yet stopped but we have always recognized that the possibility existed at any time. Events in life never stand still, and inevitably, we will need to change our lifestyle again in response to some outside influence. In our case, it will probably be that Emma exceeds our ability as educators and can benefit from a formal education. Anticipating this, near our second anniversary of travel we bought a house. It’s a small low-maintenance shelter designed specifically to give us a stable base if we need it, and designed to avoid bankrupting us if we don’t live in it.

To date, we have not moved into the house and have no immediate plans to do so. We have a choice now, between living in a traditional base with all the amenities of modern American life, or continuing on with the metaphorical traveling circus. Having the security of knowing the house is there, we choose the circus for as long as we can. There is more growing to be done, and the unexplored world still calls.

July 18, 2007 at 5:44 pm · Filed under FAQs

This is the second part in a multi-part series about how we got started as full-time Airstream travelers. The first part can be found here.

At this point Airstream Life magazine had produced just four issues and my credibility with Airstream was rising, but I am sure they did not feel responsible for my housing problems. Fortunately, Bob Wheeler, the new president of Airstream, and a few other members of senior management thought the Tour of America idea was worth a small investment. It was also fortuitous that they happened to have a trailer that would fit our needs (an Airstream Safari 30 “bunkhouse” that had been used as a demonstrator) and were willing to lend it to me on the conditions that I insure it, and either buy it or sell it to someone else in six months. I was to pick it up in October 2005.

I should pause here to mention that this is highly unusual. Being the icon of American road travel, Airstream receives literally dozens of requests for “loaners” each month, ranging from the impressive to the bizarre. With rare exceptions, these requests are turned down ““ Airstream does not have loaner trailers. In 2005, only a few trailers were made available, to high-profile TV productions (such as “The Apprentice” with Donald Trump, and “The Simple Life” with Paris Hilton) and to major promotional partners ““ and they probably had to pay for them.

Since then, I have been contacted by many wannabees who email me asking for “contact names at Airstream,” and “tips on how to get a free trailer.” Inevitably they justify this because they are going to roam the country doing something (taking photos, selling gizmos, interviewing people, visiting every flea market east of the Mississippi) and along the way they propose to “promote Airstream.” This usually doesn’t work, and in any case there are no free trailers to be had. Hey, I publish a magazine all about Airstream and still I had to promise to pay for the trailer if I couldn’t find a buyer for it. I used to try to gently dissuade people who were looking for aluminum handouts, but now I don’t respond. I hate to smash people’s dreams.

Three months before the scheduled pick-up date, our house sold. Suddenly our proposal to become “full-timers” moved from the academic to the asphalt. We moved into a 1977 Argosy trailer (the magazine’s restoration project) for the summer and stuffed our belongings into two large climate-controlled storage units. We traveled a few weeks that summer, but spent most of it parked near our former hometown, gathering steam for “the trip” we expected to begin in October.

We soon discovered that society is not geared to respect people without fixed addresses, especially people with children. We were called gypsies, nomads, wanderers, drop-outs ““ and those were the things our friends said. Others, thinking I was not overhearing their whispers, or posting comments on the Internet, were not as kind. There was a perception that by carting around our child we were unstable, denying her the right to “socialization,” denying her security, and the benefits of traditional communities: the Brownie troop, trick-or-treating, piano lessons.

I think the most cutting perception was that we had dropped out of society and were on some sort of permanent vacation, living on coconuts and love, working for gas money and sleeping in Wal-Marts to save money. For all the perceived enlightenment about telecommuting, virtual offices, and Internet-based businesses, this country has a lot of growing up to do when it comes to recognizing that most “knowledge workers” need not come into the office anymore.

When people said, “How can I reach you?” I replied with the same list of phone numbers and email addresses that I had used for two years prior. Inevitably this caused a double-take. The technology does not care if we move around, but many people still do. A full-time traveler has to come to terms with the fact that most people will not fully understand what they are up to. If you can get acceptance, that’s good enough.

Around this time I also realized that most people would never do what we were doing, even those who openly fantasized about it. When it comes to the tough choices, most people are unwilling to make the trades necessary to enable a traveling life. We traded the benefits of hearth and home for the freedom of travel, driven by a need to do something about the green hemorrhage of money caused by the business.

But I was also disenchanted by the house; it made me stay put on Saturday to mow the lawn, it needed painting, and the garden needed weeding. We might as well have justified the change on the basis of time instead of money. Money can be generated, but we all have the same amount of time in a day, and at the age of 40 I decided I wasn’t going to continue spending my time sitting on a riding lawnmower. Eleanor would have been happy to stay in the local area, but in the end it was her idea to move into the Argosy for the summer rather than rent an apartment. If we were going to live in an Airstream, she felt we should not be afraid to start right away. Without these multiple motivations, we might have thought twice about it.

It also helped that we engaged in a small self-deception: once the six month tour was over, we would return to home base and build a new house, a small one that we could easily leave behind for a few months each year without feeling undue pain of upkeep. The magazine, we surmised, would be throwing off more money by then, and we’d be comfortable taking out a new mortgage.

Anyone who has launched a small business can probably see how utterly unrealistic this was, and so can I, now. Most new magazines are gone in less than two years, victims of low advertising revenues. But at the time we were utterly inexperienced in the magazine business, perpetually optimistic about its prospects, and besides, what else could we do? The alternative was to get a real job and throw away the dream. It was more to our liking to run away with the circus and worry about the rest later. This is another aspect of the decision to travel full-time, a willingness to deny “reality” as you know it and take a leap of faith.

Without some faith in yourself, or least blindness to the many things that can go wrong, a life-changing experience will only happen by circumstance. Most such experiences have a large negative component: bankruptcy, health problems, death, corporate relocation, job loss. I’d much rather pick my own life changing experience and try to make it a good one. It takes some self-confidence, and it most definitely requires that you moderate in your mind the comments of nay-sayers. There is always a reason to not do something, and there are always plenty of people willing to explain those reasons to you. Being stubbornly unreasonable can be an asset.

… to be continued …

July 17, 2007 at 4:40 pm · Filed under FAQs

The following is the first in a multi-part essay which may — if it works — be featured in a book about our two-year trip in the Airstream. This is only the first 950 words. The rest will be posted over the next few days.

The question I am most often asked these days is simply, “How did you get started on this?” They’re talking about the fact that for the past two years I have lived and traveled across North America with my family in an Airstream trailer. For many people it is the dream life: no mortgage, no taxes, no permanent neighbors or boss, endless diversions and the ability to follow the sun. It is like having Peter Pan sweep in the door and take you to Neverland, or running away to join the circus ““ a fantasy that has its roots in our childhoods and is thus so pervasive in our psyches that we can’t shake it.

For this reason, many people either desperately aspire to become travelers, or the idea of being “rootless” is so foreign and intimidating that they are morbidly curious. Either way, I get a lot of inquiries.

I try to be honest. Even in Neverland there was Captain Hook, and if you were so lucky as to run off with the circus you might find yourself working as the clown they shoot out of the cannon nightly. But still, it is a remarkable fantasy to be free to travel and explore the world without the constraints of a fixed foundation. Prospective travelers seem to fall into three categories: those who want to get more out of life, those who are trying to fill an internal void, and those who wish to escape from a prison they’ve wrought for themselves.

It is utter nonsense, of course, to think that life “on the road” is somehow intrinsically superior to life somewhere else, if your personal demons travel with you or if you expect to find no villains as you go. I can testify to that. Our lives have been no more carefree than anyone else’s, and a good bit more complex than most. We’ve been fraught with the usual bugs of life, just as we would have been if we had stayed home. But there is something better about it, and after two years I am still not sure what it is. It’s like sitting in warm sunshine. I can feel it, but I can’t explain it unless you try it yourself.

Likewise, it has been impossible to sum up the experience of two years. Where to start? The dozens of indescribable sights? The roadschooling education of my daughter (now seven years old)? The mechanics of trailer travel? None of these things are the full story. Even explaining what we’ve learned from the experience is too much to tell, and when I try I inevitably wind up disappointing the listener.

That’s because the truth is too mundane. It has not been a singular experience since we began living in an Airstream trailer. It hasn’t even been a process. It has been life, under circumstances somewhat different than the usual, with all the joys and faults that materialize in any life. Every time I try to answer the question more cleverly, the answer goes out of my head before I start talking, which is a formula for babbling.

At one time I would toss off a blithe response to people who asked how they could travel like us, before retirement. “It’s simple,” I’d say. “Just start a travel magazine, sell your house, and buy a trailer.” But this too-glib and canned answer would inevitably disappoint as well. It was almost as if I was shrieking jealously, “You can’t! Don’t even try!” which was not my intention at all. I stopped doing this after the third or fourth bad reaction.

In reality, our trip ““ if you can call it that ““ was borne out of necessity. In 2003 I left my career as a wireless industry consultant and in early 2004 I launched Airstream Life magazine. The magazine was designed primarily to give me something to do that I would actually enjoy, with the vague hope that somewhere down the road it would also make money. By late 2004 it was clear that the work was agreeable and the finances were not. I had a choice between folding the magazine or committing to it more fully, and I chose the latter.

What is commitment? Entrepreneur magazines like to toss out this word as if commitment was a known quantity ““ either you are or you aren’t, apparently. In our case Eleanor and I justified the sale of our home by examining its true cost of ownership. It was costing us about $65 per day to live in our home, once we factored in all the costs. Eleanor checked local hotels and found a long-term stay rate at the same price ““ and for that, she pointed out, we would get a pool, maid service, and free continental breakfast. We could certainly live in an Airstream for less than that, and we’d have the bonus of being able to do a little traveling as well. So was it commitment to the magazine that made us sell the house, or a well-justified opportunity?

Regardless, a few months later I found myself in the made-over garage in Jackson Center, Ohio, that serves as marketing headquarters for Airstream Inc., pitching Airstream on the idea of lending me a trailer to take a six month “Tour of America.” I promised that I would cover the trailer in colorful vinyl graphics, blog the entire trip, write about it in the magazine, maintain a digital photo album online, and contribute articles to Airstream’s email newsletter. In short, I was desperately trying to show Airstream some value for what amounted to a housing subsidy for me, and I was scrambling for any justification I could find.

… to be continued …

« Previous entries ·

Next entries »

Lots of people use walkie-talkies but we just use hand signals like those used at the airport. Make sure you both know the proper signals and don’t spontaneously make up new ones. The signals should use your full arms, not just hands, so the driver can see them clearly. You only need four signals: left turn, right turn, come ahead, and stop. For stop, we use crossed forearms (forming an X) because they are easier to see. You might also want a fifth signal, “go ahead,” when the backing isn’t going well and you need to pull forward again.

Lots of people use walkie-talkies but we just use hand signals like those used at the airport. Make sure you both know the proper signals and don’t spontaneously make up new ones. The signals should use your full arms, not just hands, so the driver can see them clearly. You only need four signals: left turn, right turn, come ahead, and stop. For stop, we use crossed forearms (forming an X) because they are easier to see. You might also want a fifth signal, “go ahead,” when the backing isn’t going well and you need to pull forward again.