September 1, 2008 at 1:13 pm · Filed under Roadtrips

Early Sunday morning the rain began in Silverton, a tap-tap of fat drops that steadied into a drizzle by the time we got out of bed. This rain had been forecast, but the Silverton forecasts are often wrong (I was told), so I had hoped it would not come.

Our task for the day was to drive back along the Million Dollar Highway to Durango and then to Mesa Verde National Park. This is the same highway we arrived by, which meant again we needed to cross two very high passes with steep ascents and descents: Molas and Coal Bank. Now the task was complicated by wet roads and occasionally dense fog.

So we prepped everything, donned our rain gear, and said goodbye to Mike and Tracy. We expect to see them again over the winter in Tucson and perhaps Quartzsite, and even Silverton next summer.

Like bats before flight, we first stopped at a nearby campground to offload about 200 pounds of black and gray water. (Campgrounds will usually allow you use of their dump stations even if you aren’t staying there, for a fee, in this case $5.) Two hundred pounds may not seem like much in the context of a combined rig that weighs closer to 14,000 pounds, but amazingly it does help a bit with the power when climbing 7-8% grades for many miles.

Since driving conditions had the potential to be nerve-wracking as we wound up and down the steep grades with few guardrails, everyone kept silent. This is a technique used by airline pilots (the “sterile cockpit” rule, which says that there can be no unnecessary chatter on the flight deck of an airliner below 10,000 feet), and it really helps. I got the rig into a nice steady groove in second gear as we climbed out of Silverton, and we rolled along steadily until the road finally straightened out 20 miles later.

Steady is the key. A road like this is constantly inciting you to speed up on descents and slow down on ascents & curves, and if you give in to it you will find yourself either standing on the accelerator or brake nearly all the time. This is hard on the rig and can easily lead to loss of control. Remember, you’ve got thousands of pounds of cargo behind you, just aching to push you sideways on a descending turn. On a climb the engine or transmission can easily be overheated. And brakes will fade to worthlessness once they get too hot.

So we used every advantage we had. The Hensley hitch kept the trailer straight, we stayed in second gear the entire time for engine braking, and I tapped the disc brakes lightly on the descents when engine braking wasn’t enough. I kept the speed within a band from 15 MPH (on the hairpins) to 35 MPH, and watched the RPM gauge to keep the transmission in its ideal range for cooling.

Cars and motorcycles stacked up behind us, and would occasionally pass in suicide maneuvers. The entire road is a no-passing zone, for good reason. The speed limit is generally 30-35 MPH and much slower in curves. There are few pull-outs, so most of the time there’s nothing you can do about impatient people who want to shave two minutes off their trip. If you find yourself in this situation, don’t let pressure from vehicles behind cause you to drive beyond your rig’s abilities. If you are wrecked on the side of the road after going too fast on a wet foggy mountain pass, will they stop and take responsibility for it? Will they go to the hospital on your behalf, or buy you a new truck? Unless you are sure the answer to all these questions is “Yes,” let “˜em wait, or use the next available pull-out.

The only really intimidating part of the ride was one point when we were descending to a steep hairpin turn in dense fog. I could not see the turn even two hundred feet from us, but fortunately the GPS map showed me it was coming, and being in fog I already had the Nissan and Airstream slowed down to 20 MPH. Steady as she goes.

I’ve mentioned before not to trust the GPS when going to state or national parks, but I’ll say it again. Coming to Mesa Verde from the east, Garminita wanted us to exit the highway onto a dirt road named “H-5.” Knowing that she tends to get excited when we approach a national park, I disregarded this and continued another mile down the road to the proper (and well-marked) exit. Good thing, since H.5 doesn’t go anywhere. I pity the RV’er who follows that direction from their GPS. Attempting a U-turn on a narrow dirt road (or worse, backing up a half-mile) is not fun.

Mesa Verde is a large park containing over 600 cliff dwellings, 4,200 other ancient dwelling sites, and many miles of twisting roads. Those roads connect to just a handful of sites that are open to the public, and trailers or motorhomes with vehicles in tow can’t traverse them. Motorhomes over 25 feet long or 8000# GVWR are prohibited entirely from the road to Wetherill Mesa.

Even after driving five miles into the park to set the trailer in Morefield campground, it was another 11 miles to the Visitor Center, and an additional 12 miles to Wetherill Mesa, where we took our first tour of a cliff dwelling.

I had chosen to stay in the park at Morefield because (1) we always like the national park campgrounds for their convenient access, low prices, and generally attractive settings; (2) the NPS website said, “It never fills,” so even on Labor Day weekend we didn’t need to worry about reservations. Alas, Morefield was a slight disappointment. Now I know why it never fills. The price when we arrived was not $14 as published on the website, but a startling $24.05 per night. That’s a lot for an unlevel, weedy, primitive site (meaning no hookups). Bathrooms are nearby, but showers are inconveniently located over a mile away. Still, the location is at least five miles closer than the nearest commercial campground.

Since we arrived in Mesa Verde in the early afternoon, there was time to explore one end of the park. At the Farpoint Visitor Center, the road forks into two. One road leads 12 miles to Wetherill Mesa, and the other road leads 5 miles to Chapin Mesa. Although the distances don’t seem long, the twistiness of the roads means that the 12 mile drive to Wetherill takes about 30 minutes. Since there are multiple sites to visit at both mesas, and the drive times are long, it’s impossible to see everything in one day.

We caught the last (4 pm) tour of the day at Long House, the second-largest cliff dwelling in the park. It’s also the longest tour, at 90 minutes. This visit made up for the tedious drives of the day, because Long House is just spectacular. With overcast skies in the afternoon, the light was perfect. Inside the dwelling I used bounce flash to fill in a few shots, but for the most part it was just natural light. I shot over a hundred images and wished I’d had time for many more. I’ll be setting up a new album on Flickr for some of my favorites.

Getting to Long House requires a tram ride, a steep set of stairs, and a hike of about half a mile. Exactly at the end of the tour, the skies opened up and a deluge started “¦ and of course, being optimistic, we left the rain jackets back in the car. We weren’t the only ones. Half a mile later, about a dozen of us arrived at the tram stop utterly drenched, and then sat down on the flooded plastic benches of the tram for a soggy open-sided ride back to the parking lot.

The rain meant there was no chance of us attending the Ranger talk in the amphitheater at Morefield campground, so we dragged our dripping selves back to the Airstream and fired up the catalytic heater to maximum. If there’s any fun in getting soaked in the rain, it’s the moment you take off all the wet clothes and put on dry ones, while standing in front of a toasty heater.

We hung our wet stuff in front of the heater, including our shoes and Emma’s stuffed cat Zoe (she goes along for every hike and really doesn’t like getting wet), and watched a movie while eating pecan-crusted boneless trout filets that we bought at the Great Machipongo Clam Shack in Virginia last May. That made a fine end to a long and wild day, and it felt well worth the trouble of towing the Airstream over the mountains to have it waiting for us with warmth and dinner and comfort.

August 30, 2008 at 11:25 pm · Filed under Uncategorized

Our hosts Mike and Tracy have wanted to take us out on some 4WD adventures around Silverton. It’s not hard to find good 4WD roads here, in fact almost all the roads outside of the town center require 4WD. The old mining access roads that criss-cross the mountains have been claimed by the County, and are “maintained” to a relatively primitive standard for tourists and modern-day prospectors to use.

No matter where you go, you will see old stamp mills (for refining ore) or their foundations, hanging onto steep hills. There are also literally hundreds of abandoned mines and shafts. Some have been sealed by the Bureau of Mine Safety, others haven’t. (Don’t go in old mines under any circumstances.) There are also ghost towns high up in the mountains, and the remains of mining camps.

And, thankfully, there are pikas. Pikas are cute little rabbit-like creatures that inhabit high altitudes. They can’t survive in warm climates, so they are an indicator species of global warming. When temperatures go up, so do the pikas, until they can’t go up any further, and then they disappear.

And, thankfully, there are pikas. Pikas are cute little rabbit-like creatures that inhabit high altitudes. They can’t survive in warm climates, so they are an indicator species of global warming. When temperatures go up, so do the pikas, until they can’t go up any further, and then they disappear.

It turns out that pikas thrive in areas near old mines. The piles of rock and tailings give them housing and protection, and the nearby meadows provide their food. In a one-acre area near a mine at 10,500 feet, I spotted a dozen or so pikas and heard many more chirping to each other. I also spotted a few marmots, which are just fun to watch.

Paused at California Pass, alt 12,930. Note the Isuzu at center.

The 4WD roads can be intimidating. There are lots of places where the road has a steep hairpin bend and the drop-off is a thousand feet or more. I can’t count the number of times I was gripping a handhold in the Isuzu in complete terror. Fortunately, Mike is an extremely careful driver with a lot of experience in driving these roads. We wound up to a peak of 12,900 feet where the views were spectacular, and then looped around the mountains to come back to Silverton by a different approach.

You can’t really see this area without a 4WD vehicle. We could have taken the Armada, but it is too large for some of the turns. The Isuzu Trooper was a fine choice because of its small size and nimbleness, and a Jeep would have been as well. You can rent Jeeps in downtown Silverton.

View from California Pass.

At each ghost town or abandoned mine, we’d park the car and look around for a while. It’s amazing that over a century ago men somehow got up to these places above 10,000 feet, built roads and railways and trams, and managed to mine metals from hard rock mountains, all with a steam-engine-and-burro level of technology. Just walking around at these altitudes will tire you. These folks were up there living year-round in crude cabins, where snowfall is routinely dozens of feet. Just the existence of the roads is absolutely amazing when you’re up there driving on them.

At each ghost town or abandoned mine, we’d park the car and look around for a while. It’s amazing that over a century ago men somehow got up to these places above 10,000 feet, built roads and railways and trams, and managed to mine metals from hard rock mountains, all with a steam-engine-and-burro level of technology. Just walking around at these altitudes will tire you. These folks were up there living year-round in crude cabins, where snowfall is routinely dozens of feet. Just the existence of the roads is absolutely amazing when you’re up there driving on them.

By the way, Silverton is an excellent place to camp in relative seclusion if you are willing to pull your RV over a few bumpy dirt roads. Free camping is widely available on public land (as well as at three commercial campgrounds in town). “Make local inquiries,” as they say, before wandering off the beaten path.

Well, we’ve seen a fair bit of the Silverton area but there is much more. We’ll be back again. I don’t know when, but we will be back, someday.

August 30, 2008 at 10:30 pm · Filed under Uncategorized

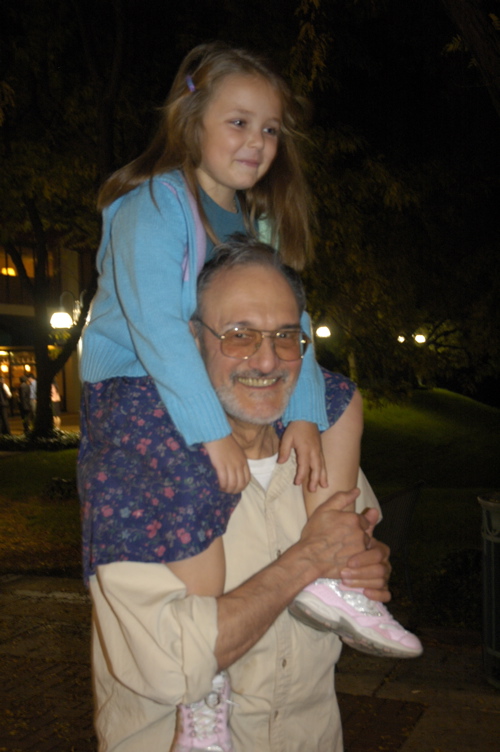

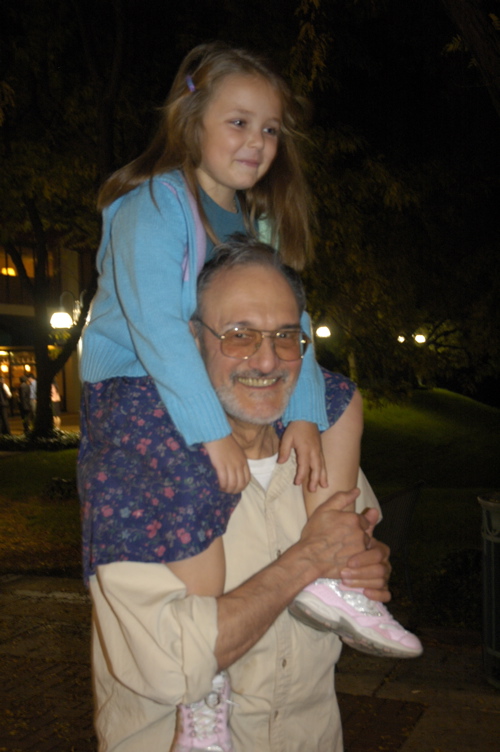

This blog entry has nothing to do with our travels, but instead someone else’s travels. I received word yesterday that our friend Herschel Shosteck succumbed to cancer.

Long-time blog readers may remember that Herschel has popped up in the blog a couple of times. I worked for Herschel from 1994 through 2003, and we traveled together on many business trips, including several trips to England, Italy, and Israel. It was a privilege to work for him, and fun to travel with him. He was highly respected in the field, and a natural teacher. The experience I gained while working in The Shosteck Group was absolutely priceless, and has served me well ever since. But by 2003, I felt burned out, and I left his firm. A few months later, I started Airstream Life and an entirely new career.

It was tough for me to leave The Shosteck Group, and I think it was hard on Herschel and Jane (his business partner) as well. We had worked closely together in an often-intense environment for nearly a decade. While there were many times when we battled, and debated in loud voices, and annoyed each other, we ultimately had become good friends. My departure was a shock for all of us, and it wasn’t on the best terms.

For while we didn’t speak to each other, and then in 2006 Jane reached out and reconnected us all, when Herschel was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer. I’m glad she did. We had the opportunity to re-start our friendships. Herschel, being a kind soul, unconditionally forgave and forgot whatever unkind things I might have said. Over the next year, I had many wonderful conversations with Herschel (now retired) as he simultaneously worked on a book and battled the cancer that he knew could not be beaten.

Being a fellow writer, I was able to review drafts of Herschel’s book about his journeys through Israel’s Negev Desert. This gave us a basis for our new relationship, and switched the roles we had traditionally had when I worked for him. Now he was the writer, and I was the editor. He very kindly incorporated all of my suggestions into his re-drafts, which is the highest form of praise an editor can get.

When we saw Herschel in 2007 for Thanksgiving dinner, he was looking superb. The cancer seemed to be at bay, at least temporarily. He was feeling reasonably energetic, enjoying a new relationship, and traveling to Europe and Israel. We talked about his travels and I encouraged him to do as much as he could. But he told me that those traveling days were soon to end. He would certainly be gone in less than three years.

Knowing that time was short, I asked for a new draft of his book, and he sent it immediately. It was greatly improved, and nearly ready for publication. I began to look forward to seeing it in print.

Shortly after, he wrote to encourage me to get on with my book:

Several hundred pages of raw materials [the blog] are a great foundation for a book. I might add to that emails as well. Every now and then people trade meaningful correspondence through the Internet — as they did during the height of the world postal systems.

I agree that editing is no less daunting than writing — in some cases even more so. Given the material you have, would it be worthwhile to extract an/some outline(s) from it? It seems that developing your theme will be the next step. What engrossing story can you pull out of the blog entries — realizing a life dream, evolving a life adventure, searching for (and hopefully finding) part of your soul, educating your daughter?

In January 2008, he wrote again:

I’m now in Silver Spring catching up on back email (note that I have only a week to go), reading, and preparing for a final edit of the manuscript. I’m also in the midst of a massive cleanup/clean-out (1-2 feet of closet or shelf space per day), in the hopes of trashing cartons of junk or transferring some of the better stuff to a community thrift shop.

My oncologist has taken me off of chemo; and with that my energy has increased to 3/4 of what it was before this mess, thus I’m able to undertake such projects. I’m almost ready to get into the last revision of my manuscript (Rev. 6.0).

But only a few weeks later, the cancer struck again, this time in his brain, and the final long decline began. I don’t know if he made any progress on Rev 6.0; all I have is Rev 5.1. The cancer stole his quality of life and eventually his intellectual mind, and the book never saw publication in print.

A version of the book is now online at www.negevjourney.com, posted by a family member. It’s not the finished version Herschel intended. (The “contact” information on the website is pointless, since it shows the postal and email addresses of a man who is now gone. Unless they’ve managed to connect Heaven to the Internet, he won’t be replying.) But if you are interested in a very intellectual tale of exploration, you might download the chapters and read it. It’s not an easy read but it is a fascinating one, both for the religious and personal revelations that he discovered in his Negev journeys.

I’m not going to point out morals to this story. I’ll just say that a good friend is gone, and I’ll miss him. You can draw your own conclusions as to what all this means to you.

August 30, 2008 at 12:30 am · Filed under Places to go

From our campsite in Silverton, “it’s up, to anywhere,” according to Mike. That’s because we are sitting in the small valley ringed by mountains of 11,000 to 12,000 feet. It may look like we are in the lowlands, but our elevation is still high enough to mess with the cooking (9,400 feet). We parked are in the middle of a flat spot just big enough for the tiny town of Silverton, a narrow-gauge railway, a river, and not much else.

If nothing else, the air would tell me that we are at high altitude. When the sun is shining through the thin atmosphere, it feels very warm, but the moment it ducks behind a cloud there’s a chill. Nighttime low temperatures are in the 30s right now, and sunlight is limited by the high mountains. In the winter, Mike says, the sun rises twice: shortly after coming up it slides behind a mountain and comes out again later.

Everything around the Airstream says we’re in an old western mining town. There are rusty metal pieces and concrete foundations left behind by miners, and mountains scarred from tailings and avalanches. The main street has old hotels and the remains of a once-thriving “red light” district. There is no consistency in architecture, and no sense of enforced historic preservation. The mere fact of utility has kept buildings in place: if it hasn’t burned down or collapsed under the snow load, why change it? We certainly aren’t in Telluride.

Silverton has two paved roads. One is the highway that brought us here, and which continues on to Ouray. The other is the main street of town, where we are parked. When the snow is deep, snowmobiles are the fastest way to get around.

It’s a relatively quiet main street because it doesn’t go anywhere. At one time the locals had a sign at the end of the street that said something like, “This isn’t the way to Ouray.” Lost tourists have to make a U-turn. The rest of the streets are dirt, giving the town a very western rural look.

This morning Mike took us on a tour of the area in his 4WD Isuzu Trooper. Seeing town doesn’t take long, but as with all the funky western towns, there are lots of little details hidden in the corners and stories to be told about the people and events that make the town interesting. And it is a very small town: the local school had 40 students (including grade school and high school) and a graduating class of 1 last year. So everyone seems to know everyone else, and if they don’t, they wave anyway.

There’s a narrow-gauge railroad that runs from Durango to Silverton, along approximately the same route that we just towed on Thursday. The train comes into Silverton twice a day, so we went over to watch it go by. I’d be tempted by the ride, but it takes several hours to make the round-trip, and the drive over is still too fresh in my mind.

Being a dyed-in-the-wool rockhound, Mike knows all the spots to find various minerals. He also knows Emma loves hunting for rocks, so a large part of our tour involved stopping at old mining sites and whacking rocks with hammers. They found some big pieces of rhodonite, but struck out on finding a good sample of “peacock copper.” It wasn’t all rocks, though. Mike was good enough to give a fair bit of mining and settlement history as we walked around the ruins of stamp mills and narrow gauge railways.

We like Silverton, so we’ve decided to postpone our departure by another day. We’ll spend Saturday much as we did today, just looking around and maybe doing some small hikes, before moving on to Mesa Verde.

August 28, 2008 at 11:38 pm · Filed under Roadtrips

We have departed the Great Sand Dunes for points west.

This has been an incredibly convenient park. Near the campground they not only have a recycling center, a bear-proof trash drop-off, a dump station, and good-tasting water, but also compressed air. It’s provided for people who have had to lower their tire pressure when driving on the sandy 4WD roads. I took the opportunity to get all of the trailer’s tires to exactly 65 psi cold, and then we headed over to the Visitor Center to show the rangers Emma’s efforts in the Junior Ranger booklet.

The rangers were suitably impressed with her work and her drawing of the dunes, and the fact that she had been in the park for three days. So they awarded the ultimate bonus of the Junior Ranger program: both a badge and a patch.

The rangers were suitably impressed with her work and her drawing of the dunes, and the fact that she had been in the park for three days. So they awarded the ultimate bonus of the Junior Ranger program: both a badge and a patch.

Our goal for the day was Silverton, where our friends Mike and Tracy live. It’s not on the way to anything we had planned to see, but the opportunity to enjoy their hospitality and local guidance was worth wandering 50 miles off course.

Driving around Colorado means you’ll eventually have to cross a mountain pass. The big ones all have names, and you’ll remember them, because each pass has its own personality. They vary in steepness, length, height, and fear factor, but they are all memorable.

In our travels we have crossed some doozies. Slumgullion Pass on the road between Durango and Creede was really a nail-biter. Monarch Pass was memorable for the aerial tramway we rode at the 11,000 foot summit. At those altitudes the gas-powered Nissan doesn’t put out its full power, so we generally gear down to 2nd and roll up the mountain grades at 35 to 40 MPH. That’s fine, since the speed limits on the twisting state highways leading toward passes are usually about 45 MPH, and slower in the hairpin curves.

Today we set a record: three passes in one trip segment. The first was Wolf Creek Pass, about 9,400 feet. The second was Coal Bank Pass, at 10,600 feet, and the third (right on the heels of Coal Bank) was Molas Pass at 10,800 feet. At Molas the summit feels like you’re on the top of the world. Ten thousand foot peaks are scattered around below you, and vast deep valleys are far below.

Of course, what goes up must go down, and that means four or five miles of 7-8% descent. That’s enough to smoke your brakes if you aren’t careful. Our procedure has been to keep the truck in 2nd and tap the disc brakes once in a while to keep the speed under 40 MPH, and 25 MPH in the curves.

Coal Bank is right up there with Slumgullion for sheer terror. Much of the road involves incredibly long drops off the non-existent shoulder, and there are few guard rails. Cross the white line with a wheel and it will be the last thing you do. I kept my eyes focused on the road and tried not to look down the steep embankments, although Eleanor was right there with a running commentary about the cliffs.

After that experience, we were glad to wind down into the little former mining town of Silverton, where Mike and Tracy live part of the year in a little century-old house on the main street of town. (When they are not here, they’re off in their Airstream Classic motorhome, which for the record goes up Coal Bank Pass at about 20 MPH. Mike says, “I’m the guy I used to be stuck behind when I was younger.”)

We’ve been given a fine courtesy parking spot next to the house, and an invitation to stay up to 20 days, the legal limit here. We’ll probably stay two or three days, although I could certainly yield to the temptation to stay longer. Even with only a couple of hours before sunset, I could see that Silverton has a lot of things to explore: historic architecture, hummingbirds, hiking, 4WD explorations, abandoned mines, local characters, etc. We’ll start checking it all out on Friday.

August 28, 2008 at 10:26 am · Filed under Places to go

Coming to high altitude areas and hiking requires some acclimation. Normally we are above 5000 feet for at least a few weeks before we attempt hiking in the mountains, but this time it didn’t work out that way. So when we started climbing up giant sand dunes in the morning, it was more of a challenge than you’d think.

The dunes are mammoth, with the big ones running 600-750 feet tall. The big ones are surrounded by foothills of sand, so at first the climbing doesn’t seem that bad. But being made of shifting sand, there is no trail, and it’s easy to summit a sandy peak only to find that a massive canyon lies between you and the next dune.  After about 90 minutes of zig-zagging across the steep slopes, we finally reached the top of one of the higher dunes, and stopped for a snack, some oxygen, and a quiet look at the gorgeous view.

After about 90 minutes of zig-zagging across the steep slopes, we finally reached the top of one of the higher dunes, and stopped for a snack, some oxygen, and a quiet look at the gorgeous view.

Hiking in the dunes can be extremely arduous and even dangerous under some conditions. Summer temperatures on the dunes can reach 140 degrees, and thunderstorms are common. If you’re on the dunes during lightning, you may have a bad day ““ and it’s hard to escape quickly. For these reasons we went out in the morning, and were lucky enough to enjoy absolutely spectacular weather and crystal visibility.

Water and sunscreen are the other keys. It’s like being on a sunny beach, only with no shoreline. Bring a lot of water on a warm day. Don’t be fooled by the green pines that cover the mountains. The dunes are a desert environment. I filled my 100-oz Camelbak and the three of us drained it in about three hours, plus some additional 16-oz bottles. The problem with the sunscreen is that the sand sticks to it, but there’s no point in worrying about that. You’ll come out of the dunes with sand in every possible location anyway.

Water and sunscreen are the other keys. It’s like being on a sunny beach, only with no shoreline. Bring a lot of water on a warm day. Don’t be fooled by the green pines that cover the mountains. The dunes are a desert environment. I filled my 100-oz Camelbak and the three of us drained it in about three hours, plus some additional 16-oz bottles. The problem with the sunscreen is that the sand sticks to it, but there’s no point in worrying about that. You’ll come out of the dunes with sand in every possible location anyway.

While it hasn’t been extremely hot, we took the middle of the day off from hiking and stretched out in the Airstream. Like other western parks, there are higher altitude spots to go when the heat is oppressive. In the afternoon we chose Zapata Falls (just outside the park entrance). To get there, you drive up a winding rocky road to a trailhead at about 9000 ft, then hike up further on a half mile trail to a refreshing mountain creek in the trees.

This is where it gets interesting. Zapata Falls are inside a very narrow gorge, and the only way to see the falls is to hike upstream a short distance through icy cold water. The creek narrows to a slot in the rock, and after passing through that you can glimpse the water falling. Since you do this while standing in calf-deep water that makes your feet go numb, the visit is brief. But it’s worth the trip. The hike also offers some nice views of the Dunes from above.

This is where it gets interesting. Zapata Falls are inside a very narrow gorge, and the only way to see the falls is to hike upstream a short distance through icy cold water. The creek narrows to a slot in the rock, and after passing through that you can glimpse the water falling. Since you do this while standing in calf-deep water that makes your feet go numb, the visit is brief. But it’s worth the trip. The hike also offers some nice views of the Dunes from above.

As a wind-down, we drove down the Medano Primitive Road in the park to get a different perspective on the dunes. Ordinary cars can traverse the first mile of the road, but then it becomes 4WD only. If you want a long 4WD adventure, you can go 12 miles all the way up to a mountain pass above 9000 ft and then hike another 1900 feet of elevation to a lake. That’s one I’d like to try.

The hiking here has been great, and if we had another full day we’d take one of the longer alpine trails up into the Sangre de Cristo Range. Despite the challenge of acclimating to steep hikes about 9000 feet, we all really like this park. I think we will come back.

August 27, 2008 at 10:06 am · Filed under Places to go

As national parks go, Great Sand Dunes may be underrated. We had put it on our itinerary as a side trip from the drive across southern Colorado, figuring that it would be one of those parks that has one predominant feature and not much else. After all, it’s just a bunch of big piles of sand, right?

Turns out there’s a lot more here than that. Yes, there are enormous sand dunes, up to 750 feet tall, in a huge field just a short hike from the campground. But being bordered by both desert and the tall Sangre de Cristo mountain range, the environment is very diverse and there’s a lot to see, and a lot of great hiking.

We weren’t sure when we arrived if we could actually camp in the park. The sites are generally short, meaning better suited to tents and small RVs. Big motorhomes have to camp at the Oasis Motel & RV Park just outside the park entrance. But most of the national park campground was vacant when we arrived, and eventually we shoehorned the Airstream and the Nissan into one of the larger spaces. The site slopes upward a lot, and the trailer definitely a bit higher on the front end, but it’s comfortable enough and the view of the dunes is spectacular. (No hookups, dump station, $14.) Plus we can hike to the dunes right from the Airstream’s door.

We weren’t sure when we arrived if we could actually camp in the park. The sites are generally short, meaning better suited to tents and small RVs. Big motorhomes have to camp at the Oasis Motel & RV Park just outside the park entrance. But most of the national park campground was vacant when we arrived, and eventually we shoehorned the Airstream and the Nissan into one of the larger spaces. The site slopes upward a lot, and the trailer definitely a bit higher on the front end, but it’s comfortable enough and the view of the dunes is spectacular. (No hookups, dump station, $14.) Plus we can hike to the dunes right from the Airstream’s door.

The geology of the dunes is interesting. The park has an very good Visitor Center, where you discover how the sand blows in from the San Juan Mountains to the west, drains down in creeks from the east, and then gets trapped here at the foothills. Two creeks circle the dunes, picking up any “escaped” sand and dragging it to the southwest side, where the winds redeposit it on the dune field.

Always eager to hear it from directly from the Rangers, we went to a scheduled sunset walk on the Wellington Ditch Trail, but there were thunderstorms in the area and the Ranger never showed up. Since the storms were heading away (all we got was about one minute of pea-sized hail), we hiked the trail ourselves, and then dropped in to the amphitheater for an 8:15 Ranger talk.

The wildlife here is also interesting. Down in the dunes there are species that only exist here, such as the Great Sand Dunes Tiger Beetle, and through the foothills and lower alpine area there are black bears (bear-proof food boxes are in every campsite), deer and mountain lions. A black bear was spotted in the afternoon crossing the road between the campground and Visitor Center. On the other side of the dunes, the Nature Conservancy manages a herd of over 1,000 buffalo.

The wildlife here is also interesting. Down in the dunes there are species that only exist here, such as the Great Sand Dunes Tiger Beetle, and through the foothills and lower alpine area there are black bears (bear-proof food boxes are in every campsite), deer and mountain lions. A black bear was spotted in the afternoon crossing the road between the campground and Visitor Center. On the other side of the dunes, the Nature Conservancy manages a herd of over 1,000 buffalo.

Up in the alpine areas there are marmots, bighorn sheep, and pikas, plus a very unusual salamander that actually survives the high-altitude winter by allowing itself to be frozen. The Ranger at the amphitheater talk had one and Emma was thrilled to hold the 7-inch creature in her hands (with gloves, since skin oils are toxic to the salamander).

The park was expanded in 2000 to include a chunk of the Sangre de Cristo range, which protects some of the area that contributes to the dune (adding, “and Preserve” to the official name). This expansion gives the park an enormous added dimension of mountain hikes and 4WD roads, which is what gives it a much greater status in my opinion.

With that addition, the park is more than just a place to hike around on some big sand dunes. There are some really impressive hikes up to high altitude, both easy and hard to complete. You can drive up from the base elevation of about 8400 feet, where we are camped, to mountain passes at 9900 feet, and then hike 2000 feet further up to a mountain lake, or you can just start hiking from several other points and get great views of the dunes without a lot of elevation gain.

At this point we have already decided to extend our one-night stay to two nights. It would be easy to stay here for several days or a week if we were going to tackle some of the big hikes, but I am under work pressure and need to get to a place where I can get online a little better for a few days. Cellular Internet works here, amazingly, but slowly. Two nights will have to do, and I’ll make a note that the next time we come to Great Sand Dunes, we should bring full backpacking gear for a few days of hiking.

« Previous entries ·

Next entries »